Use the definitions to verify that \(1/x^2 \ll 1/x\text{.}\)

Unit 6.3 Comparisons elsewhere and orders of closeness

Everything we have discussed in this section has referred to limits at infinity. Also, all our examples have been of functions getting large, not small, at infinity. But we could equally have talked about functions such as \(1/x\) and \(1/x^2\text{,}\) both of which go to zero at infinity. It probably won’t surprise you to learn that \(1/x^2\) is much smaller than \(1/x\) at infinity.

Checkpoint 109.

These same notions may be applied elsewhere simply by taking a limit as \(x \to a\) instead of as \(x \to \infty\text{.}\) The question then becomes: is one function much smaller than the other as the argument approaches \(a\text{?}\) In this case it is more common that both functions are going to zero than that both functions are going to infinity, though both cases do arise. Remember: at \(a\) itself, the ratio of \(f\) to \(g\) might be \(0/0\) or \(\infty/\infty\text{,}\) which of course is meaningless, and can be made precise only by taking a limit as \(x\) approaches \(a\text{.}\)

The notation, unfortunately, is not built to reflect whether \(a = \infty\) or some other number. So we will have to spell out or understand by context whether the limits in the definitions of \(\ll\) and \(\sim\) are intended to occur at infinity or some other specificed location, \(a\text{.}\)

Example 6.15.

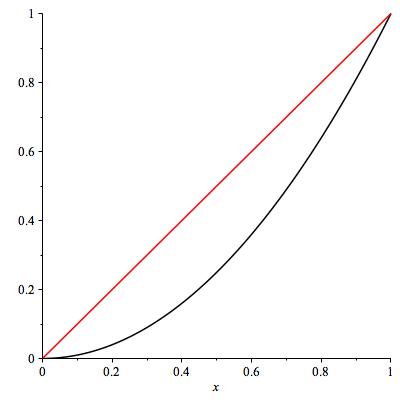

Let’s compare \(x\) and \(x^2\) at \(x=0\text{.}\) At infinity, we know \(x \ll x^2\text{.}\) At zero, both go to zero but at possibly different rates. Have a look at Figure 6.16. You can see that \(x\) has a postive slope whereas \(x^2\) has a horizontal tangent at zero. Therefore, \(x^2 \ll x\) as \(x \to 0^+\text{.}\) You can see it from Figure 6.16 or from L’Hôpital:

\begin{equation*}

\displaystyle\lim_{x \to 0^+} \frac{x^2}{x} = \lim_{x \to 0^+} \frac{2x}{1} = 0 \, .

\end{equation*}

Example 6.17.

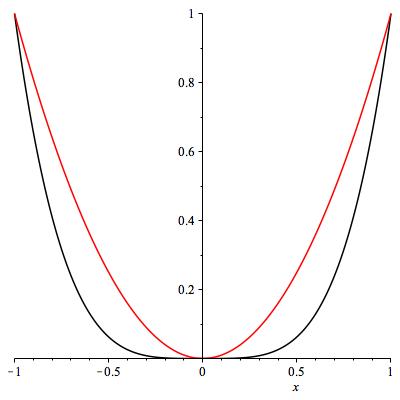

What about \(x^2\) and \(x^4\) near zero? Both have slope zero. By eye, \(x^4\) is a lot flatter. Maybe \(x^4 \ll x^2\) near zero. It is not clearly settled by the picture (do you agree? see Figure 6.18), but the limit is easy to compute.

Checkpoint 110.

Here is a less obvious example, still with powers.

Example 6.19.

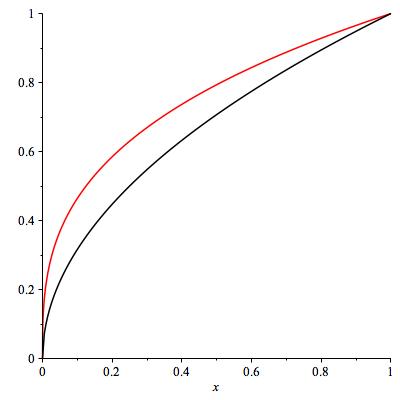

Let’s compare \(\sqrt{x}\) and \(\sqrt[3]{x}\) near zero. See Figure 6.20. Is one of these functions much smaller than the other as \(x \to 0^+\text{?}\) Here, the picture is pretty far from giving a definitive answer!

We try evaluating the ratio: \(f(x) / g(x) = x^{1/2} / x^{1/3}

= x^{1/2 - 1/3} = x^{1/6}\text{.}\) Therefore,

\begin{equation*}

\displaystyle\lim_{x \to 0^+} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} =

\lim_{x \to 0^+} x^{1/6} = 0

\end{equation*}

and indeed \(x^{1/2} \ll x^{1/3}\text{.}\) Intuitively, the square root of \(x\) and the cube root of \(x\) both go to zero as \(x\) goes to zero, but the cube root goes to zero a lot slower (that is, it remains bigger for longer).

Checkpoint 111.

Suppose \(f\) and \(g\) are two nice functions, both of which are supposed to be approximations to some more complicated function \(H\) near the argument \(a\text{.}\) The question of whether \(f - H \ll g - H\text{,}\) or \(g - H \ll f - H\text{,}\) or neither as \(x \to a\) is particularly important because it tells us whether one of the two functions \(f\) and \(g\) is a much better approximation to \(H\) than is the other. We will be visiting this question shortly in the context of the tangent line approximation, and again later in the context of Taylor polynomial approximations.

"For sufficiently large \(x\)".

Often when discussing comparisons at infinity we use the term "for sufficiently large \(x\)". That means that something is true for every value of \(x\) greater than some number \(M\) (you don’t necessarily know what \(M\) is). For example, is it true that \(f \ll g\) implies \(f < g\text{?}\) No, but it implies \(f(x) < g(x)\) for sufficiently large \(x\text{.}\) Any limit at infinity depends only on what happens for sufficiently large \(x\text{.}\)

Example 6.21.

We have seen that \(\ln x \ll \sqrt{x - 5}\text{.}\) It is not true that \(\ln 6 < \sqrt{6-5}\) (the corresponding values are about \(1.8\) and 1) and it is certainly not true that \(\ln 1 < \sqrt{1-5}\) because the latter is not even defined. But we can be certain that \(\ln x < \sqrt{x-5}\) for sufficiently large \(x\text{.}\) The crossover point is between 10 and 11.