Write a sentence for each of the two rows explaining how it establishes an area formula. What is being asserted to have the same area as what, why is this true, and what is the conclusion?

Unit 10.1 Area

Integrals compute many things, the most fundamental of these being area. The definition of area is more subtle than one might think. Most people’s understanding of area is based on a physical concept of how much two-dimensional space is taken up. For example, if you have to paint an irregular flat shape, how much paint does it take?

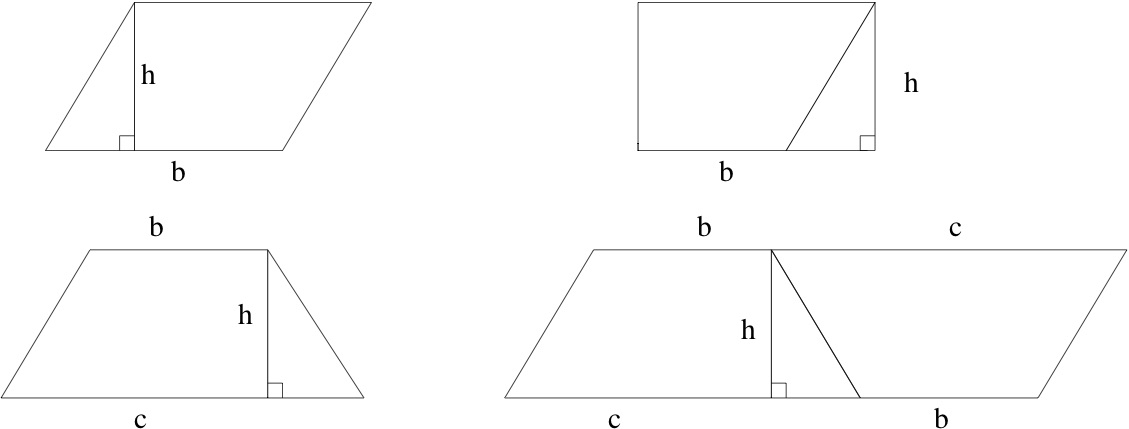

Looking back at the treatment of area in the pre-college math curriculum, you can see the steps toward a mathematical definition. First, for rectangles with integer sides \(a\) and \(b\text{,}\) you can count the number of \(1 \times 1\) squares needed to make the rectangle, leading to the area formula \(A = a \times b\text{.}\) From the physical point of view this is a formula, but from the mathematical point of view it is a definition, extended later to non-integer side lengths. Areas of triangles are not studied until much later. For right triangles with sides \(a\) and \(b\) and hypotenuse \(c\text{,}\) the area is shown to be equal \(ab/2\) by showing that two of these fit together to make an \(a \times b\) rectangle. This invokes a new principle: areas of congruent figures are equal. To compute the area of a parallelogram or trapezoid, the dissection principle is invoked: cutting up and rearranging the pieces of a figure preserves the area. These principles, all of which make intuitive and physical sense, are illustrated in Figure 10.1.

identifying congruent pieces of a dissection to evaluate areas of parallelograms and trapezoids

Checkpoint 148.

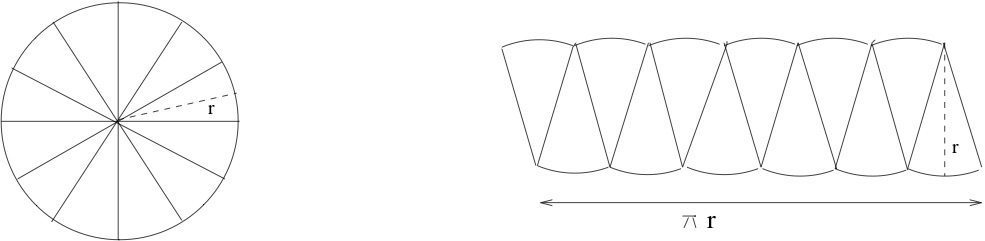

The area of a circle is introduced, usually without much explanation. Do you know why the area of a circle of radius \(r\) is equal to \(\pi r^2\text{?}\) One common explanation is that areas of similar figures are related by a scaling principle. Recalling that area has units of squared length, it makes sense that scaling a figure by \(\lambda\) should scale the area by \(\lambda^2\text{.}\) All circles are similar; if follows that the area of a circle should be \(K r^2\) for some constant \(K\text{.}\) We can name this constant \(\pi\) but that leaves a nagging question unanswered. Scaling also shows that the circumference of a circle should be proportional to the radius, therefore \(C = K' r\) for some other constant \(K'\text{.}\) This turns out to be \(2 \pi\text{.}\) But why should \(K'\) be double \(K\text{?}\) An argument involving dissections and limits is shown in Figure 10.2.

a limit of dissections relates the constants for circumference and area

Checkpoint 149.

In Figure 10.2 the measure \(\pi r\) on the right refers to the total curved length of the bottom.

We have not defined limits of shapes, but intuitively, what is the limiting shape on the right?

What are its dimensions? by

Once limits are brought into the discussion, there is a way to define areas of much more general shapes. The idea is this: put as many non-overlapping squares of some small side length \(\varepsilon\) as you can inside the shape. These cover an area less than the area of the shape, but if \(\varepsilon\) is small, it seems credible that the area is getting close to the area of the shape. If the limit as \(\varepsilon \to 0^+\) exists, this should be the area of the shape. Similarly, you could completely cover the shape with squares of side \(\varepsilon\) if you are willing to cover a slightly too big region. When \(\varepsilon\) is small, you don’t cover too much extra area. The limit as \(\varepsilon \to 0^+\) should also be the area of the shape. To make a long story short (you can hear the full story in Math 360), there are many shapes for which it is possible to prove that these two limits exist and are equal. For these shapes we can define area to be this common limiting value. This mathematical definition captures our existing physical intuition and is also consistent with the principles we already adpoted: congrunce, scaling and dissection.