Unit 1.3 Inverse functions

One method of solving the problem of Galileo’s experiment involved an inverse function. Let’s be explicit about the definitions involved. The inverse function of a function \(f \) is the function that answers the question,

What input do I need to get the given output?

In other words, if \(g \) is the inverse function of \(f \) then \(g(y) \) is whatever value \(x \) satisfies \(f(x) = y \text{.}\) If there is more than one answer to this, then \(f \) has no inverse function; however, you can usually restrict the domain so there is only one answer. If there is no answer, that’s not a problem, it just means that \(y \) is not in the domain of \(g \text{.}\) This happens when \(y \) is not in the range of \(f \text{.}\) Thus, the domain of \(g \) is the range of \(f \text{.}\) Likewise, the range of \(g \) is any possible answer to the question above, therefore any \(x \) in the domain of \(f \text{.}\)

Checkpoint 26.

The usual notation for the inverse function to \(f \) is \(f^{-1} \text{.}\) This is terrible notation because it is the same as the notation for the \(-1 \) power of \(f \text{,}\) also known as \(1/f \text{.}\) We tried changing the inverse function notation to \(f^{\rm inv} \) for the purposes of this class, but then students were confused when they saw \(f^{-1} \text{.}\) We will stick with the terrible notation, and mention it when confusion might arise.

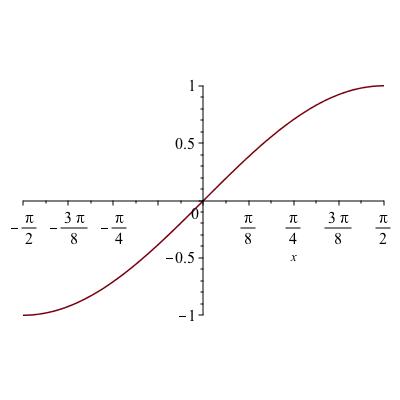

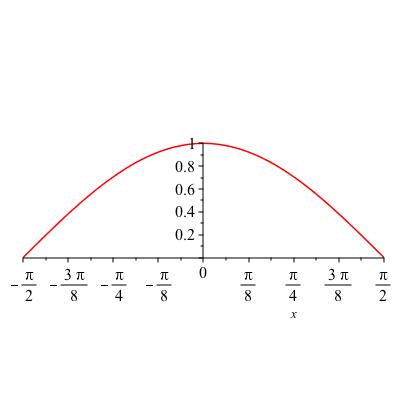

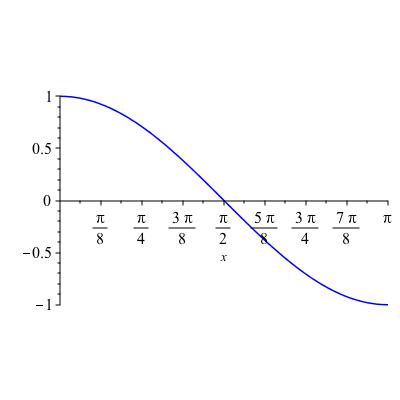

There is a standard way that the domain is restricted on trig functions so that the inverse function can be defined. For \(\sin \) and \(\tan \) it is \([-\pi/2 , \pi/2] \text{.}\) The function \(\cos \) when restricted to \([-\pi/2,\pi/2] \) is not one-to-one; the standard choice for \(\cos \) is \([0,\pi] \text{.}\) These are arbitrary conventions, but are probably built in to your calculator, so we had better adopt them. Also, along with \(\sin^{-1} \text{,}\) \(\cos^{-1} \) and \(\tan^{-1} \text{,}\) the conventional names \(\arcsin, \arccos \) and \(\arctan \) are also used.

Checkpoint 27.

Inverse functions occur naturally in mathematical modeling. For example, if \(f(t) \) represents how many miles you can walk in \(t \) hours, then \(f^{-1} (x) \) represents how many hours it takes you to walk \(x \) miles. Note that in this explanation, \(x \) is a bound variable; we could have used any other name, such as \(t \) again, only it helps readability if we use names such as \(t \) for time and \(x \) for distance.

Checkpoint 28.

Define \(f(x)\) to be the number of pounds you have to carry when planning a backpacking excursion for \(x\) days.

-

What are the units of \(v\text{?}\)

-

What are the units of \(f^{-1}(v)\text{?}\)

-

Give an interpretation for \(f^{-1}(v)\)

-

Between \(f^{-1} (v) + f^{-1} (w)\) and \(f^{-1} (v+w)\text{,}\) which do you think would be greater?

Remark 1.10.

-

The concept of an inverse function appears to be harder than most people realize. For example, a number of years ago, calculus students were given the problem to compute a formula for the inverse function to \(\sinh (x) \text{,}\) the hyperbolic sine function. This was already not easy: (only half the students got it) but then we asked them to find a number \(u \) such that \(\sinh (u) = 1 \text{.}\) Almost no one got it, despite that fact that this was supposed to be the easy part -- they just needed to plug in 1 to their inverse sinh function! By definition, \(\sinh^{-1} (1) \) is a number \(u \) such that \(\sinh (u) = 1 \text{.}\) The moral of the story is, don’t lose sight of the meaning of an inverse function when doing computations with them.

-

How does the graph of an inverse function relate to the graph of a function? The roles of \(x \) and \(y \) have switched. When the first and second coordinate of an ordered pair are switched, the point reflects across the diagonal line \(y=x \text{.}\) Thus, the graph of the inverse function is the original graph (on the appropriate domain) reflected across the diagonal.

Logarithm Cheat Sheet.

The inverse function to \(f(x):=e^x\) is called the natural logarithm \(\ln\text{.}\) All that means is: the equations

\begin{equation*}

y=e^x

\end{equation*}

and

\begin{equation*}

\ln y=x

\end{equation*}

mean exactly the same thing. Logarithms look scary, but all you have to remember is: when you see a logarithm on one side, just convert the whole equation to exponentials.

It may be useful to have some approximate values of \(\ln\) in mind so that the function seems less mysterious. The following values are accurate to about 1%:

\begin{align*}

e \amp \approx 2.7\\

\ln (2) \amp \approx 0.7 \\

\ln (10) \amp \approx 2.3 \\

\log_{10} (2) \amp \approx 0.3 \\

\log_{10} (3) \amp \approx 0.48 \\

e^3 \amp \approx 20

\end{align*}

Checkpoint 29.

In the list of approximations above, convert each statement about logarithms into the corresponding statement about exponentials, and vice versa.

In case you need them, here are some other useful quantities to within 1%:

\begin{align*}

\pi \amp \approx \frac{22}{7} \\

\sqrt{10} \amp \approx \pi \\

\sqrt{2} \amp \approx 1.4 \\

\sqrt{1/2} \amp \approx 0.7 \\

e^8 \amp \approx 3000

\end{align*}

Also useful sometimes: \(\sqrt{3} = 1.732\ldots \) and \(\sqrt{5} = 2.236\ldots \) both to within about \(0.003\% \text{.}\)

Checkpoint 30.

Squares and Powers of 2 Cheat Sheet.

If you know the powers of 2 you can do the same thing with \(\log_2 \) that you can do with \(\log_{10} \text{.}\) It will be helpful for you be at least somewhat familiar with them -- for example, to recognize them on sight. You should also recognize the first twenty squares:

\begin{equation*}

1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81, 100, 121, 144, 169, 196,

225, 256, 289, 324, 361, 400 \, .

\end{equation*}

No kidding, when you come across one of these numbers under a radical, you know immediately it can be factored out.

Here are the powers of 2.

\begin{align*}

2^0 \amp = 1 \\

2^1 \amp = 2 \\

2^2 \amp = 4 \\

2^3 \amp = 8 \\

2^4 \amp = 16 \\

2^5 \amp = 32 \\

2^6 \amp = 64 \\

2^7 \amp = 128 \\

2^8 \amp = 256 \\

2^9 \amp = 512 \\

2^{10} \amp = 1,024\\

2^{11} \amp = 2,048 \\

2^{12} \amp = 4,096 \\

2^{13} \amp = 8,192 \\

2^{14} \amp = 16,384 \\

2^{15} \amp = 32,768 \\

2^{16} \amp = 65,536 \\

2^{20} \amp \approx 1,000,000 \\

2^{30} \amp \approx 1,000,000,000 \\

2^{100} \amp \approx 10^{30}

\end{align*}