Definition 2.4.

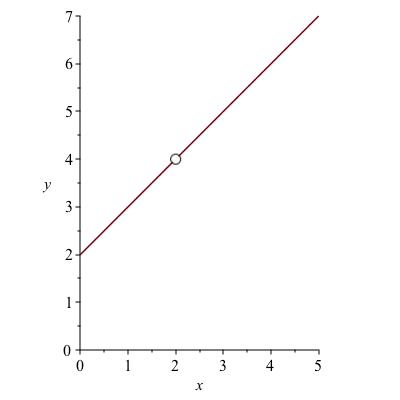

If \(f \) is a function whose domain includes an interval containing the real number \(a \text{,}\) we say that \(\displaystyle\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L\) if and only if the following statement is true.

For any positive real number \(\varepsilon \) there is a corresponding positive real \(\delta \) such that for any \(x \) other than \(a \) in the interval \((a-\delta , a+\delta) \text{,}\) \(f(x) \) is guaranteed to be in the interval \((L - \varepsilon , L + \varepsilon) \text{.}\)

In symbols, the logical implication that must hold is:

\begin{equation*}

0 \lt \left\lvert x - a\right\rvert \lt \delta \Longrightarrow \left\lvert f(x) - L\right\rvert \lt \varepsilon \, .

\end{equation*}