You may have noticed in the examples above that there’s a lot of handwaving going on with counting degrees and figuring out which terms we need to pay attention to and which we can disregard. There’s a nice method to do this accounting, but it requires a little mental flexibility.

Definition 14.14.

The Taylor series for a function \(f(x)\text{,}\) centered at \(x=c\text{,}\) is the sum

\begin{equation*}

f(c)+f'(c)(x-c)+\frac{1}{2}f''(c)(x-c)^2+\frac{1}{3!}f'''(c)(x-c)^3+\cdots

\end{equation*}

That is, the Taylor series is just a Taylor polynomial that doesn’t stop.

When \(c=0\text{,}\) we call this the Maclaurin series:

\begin{equation*}

f(0)+f'(0)x+\frac{1}{2}f''(0)x^2+\frac{1}{3!}f'''(0)x^3+\cdots

\end{equation*}

The sum in

Definition 14.14 has infinitely many terms, so you might think we’re going to veer off into questions of whether or not it converges. That’s a topic for MATH 1080. But for right now, we’re just going to

use Taylor series without caring too much.

So, for example, we can write

\begin{equation*}

e^x=1+x+\frac{1}{2}x^2+\frac{1}{3!}x^3+\frac{1}{4!}x^4+\cdots

\end{equation*}

and

\begin{equation*}

\cos(x)=1-\frac{1}{2}x^2+\frac{1}{4!}x^4-\frac{1}{6!}x^6+\cdots

\end{equation*}

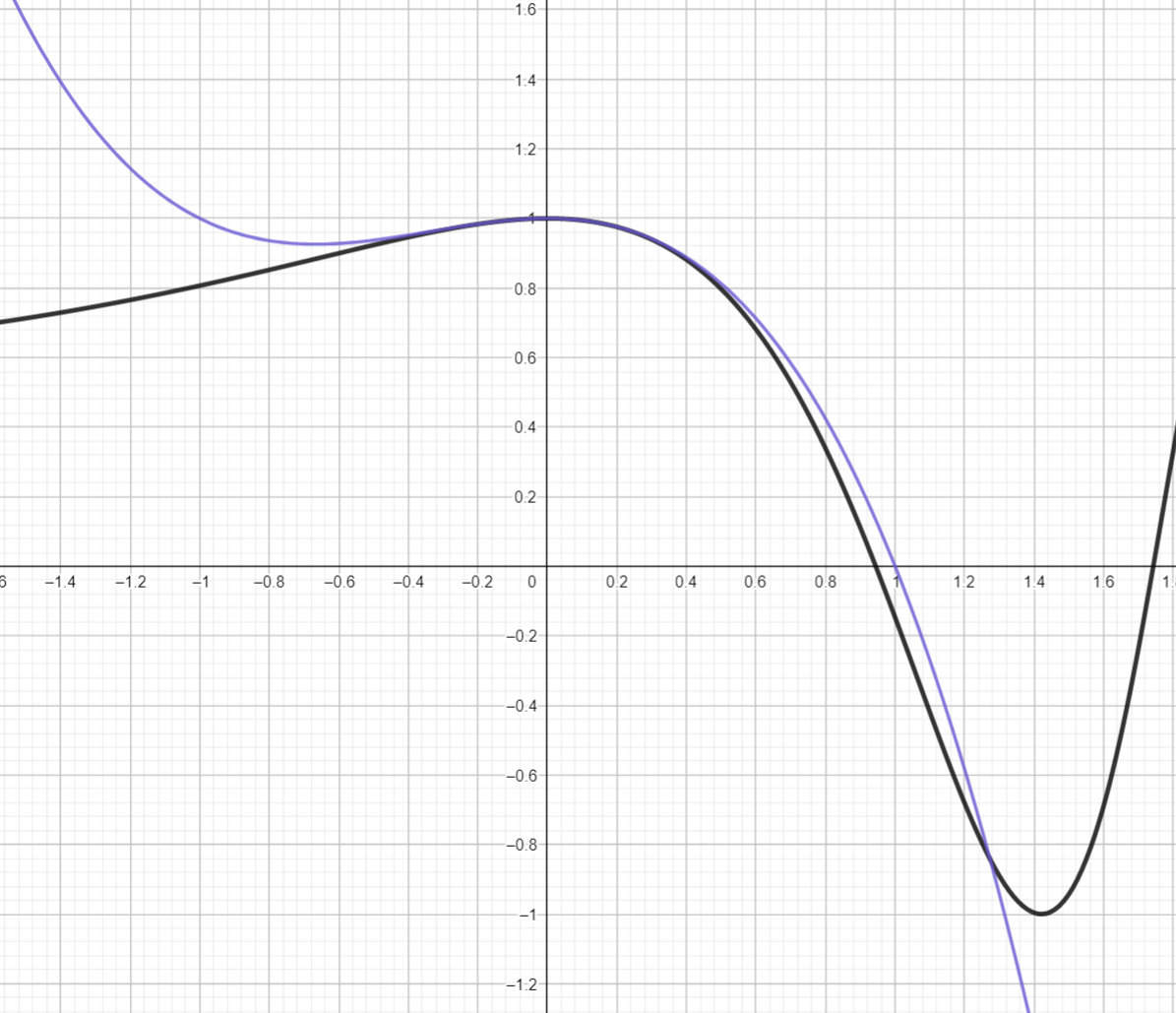

Example 14.16.

Let’s compute the degree-4 Maclaurin polynomial for \(f(x)=e^{\sin x}\text{.}\) We know that

\begin{equation*}

e^t=1+t+\frac{1}{2!}t^2+\frac{1}{3!}t^3+\frac{1}{4!}t^4\cdots

\end{equation*}

so we "just" plug in \(t=\sin x\text{:}\)

\begin{equation*}

e^{\sin x}=1+\sin x+\frac{1}{2!}(\sin x)^2+\frac{1}{3!}(\sin x)^3+\cdots

\end{equation*}

and then we "just" plug in the fact that and \(sin(x)=x-\frac{1}{3!}x^3+\frac{1}{5!}x^5-\frac{1}{7!}x^7+\cdots\text{:}\)

\begin{align*}

e^{\sin x}=&1+\left(x-\frac{1}{3!}x^3+\frac{1}{5!}x^5-\frac{1}{7!}x^7+\cdots\right)\\

&+\frac{1}{2!}\left(x-\frac{1}{3!}x^3+\frac{1}{5!}x^5-\frac{1}{7!}x^7+\cdots\right)^2\\

&+\frac{1}{3!}\left(x-\frac{1}{3!}x^3+\frac{1}{5!}x^5-\frac{1}{7!}x^7+\cdots\right)^3\\

&+\frac{1}{4!}\left(x-\frac{1}{3!}x^3+\frac{1}{5!}x^5-\frac{1}{7!}x^7+\cdots\right)^4\\

&+\cdots

\end{align*}

Now we have some algebraic work to do. We’ve been asked to look at the degree-4 part of all this, so anything with a power of \(x\) greater than 4 is irrelevant to us. That means the interior \(\cdots\text{,}\) which have a minimum degree of 9, don’t concern us. Furthermore, the terms involving \(x^5\) and \(x^7\) already have too high a degree. So we can toss those into the \(\cdots\text{,}\) too, leaving the much-cleaner-looking

\begin{align*}

e^{\sin x}=&1+\left(x-\frac{1}{3!}x^3+\cdots\right)\\

&+\frac{1}{2!}\left(x-\frac{1}{3!}x^3+\cdots\right)^2\\

&+\frac{1}{3!}\left(x-\frac{1}{3!}x^3+\cdots\right)^3\\

&+\frac{1}{4!}\left(x-\frac{1}{3!}x^3+\cdots\right)^4\\

&+\cdots

\end{align*}

Let’s take a look at the second line. Expanding it out using the formula \((a+b)^2=a^2+2ab+b^2\text{:}\)

\begin{equation*}

\frac{1}{2!}\left(x-\frac{1}{3!}x^3+\cdots\right)^2=\frac{1}{2!}\left(x^2-\frac{2}{3!}x\cdot x^3+\left(\frac{1}{3!}x^3\right)^2\right)

\end{equation*}

and the last term, \(\left(\frac{1}{3!}x^3\right)^2\text{,}\) has degree 6 -- more than we care about. So this line contributes

\begin{equation*}

\frac{1}{2!}x^2-\frac{2}{2!3!}x^4+\cdots

\end{equation*}

In the third line, we need to use the formula \((a+b)^3=a^3+3a^2b+3ab^2+b^3\text{:}\)

\begin{align*}

\frac{1}{3!}&\left(x-\frac{1}{3!}x^3+\cdots\right)^3\\

&=\frac{1}{3!}\left(x^3-\frac{3}{3!}x^2\cdot x^3+3\left(\frac{1}{3!}\right)^2 x\cdot x^6-\left(\frac{1}{3!}\right)x^9\right)+\cdots

\end{align*}

Here the terms have degrees 3, 5, 7, and 9 respectively. Only the first is relevant to us.

For the fourth line, the algebra we need is

\((a+b)^4=a^4+4a^3b+6a^2b^2+4ab^3+b^4\) and hopefully you can see that again on the first term is relevant to us.

Putting it all together yields

\begin{equation*}

1+x-\frac{1}{3!}x^3+\frac{1}{2!}x^2-\frac{2}{2!3!}x^4+\frac{1}{3!}x^3+\frac{1}{4!}x^4

\end{equation*}

which we ought to clean up to

\begin{equation*}

1+x+\frac{1}{2!}x^2+\left(\frac{1}{4!}-\frac{1}{3!}\right)x^4

\end{equation*}