Section 7.1 Defining the Definite Integral

Checkpoint 7.1.1.

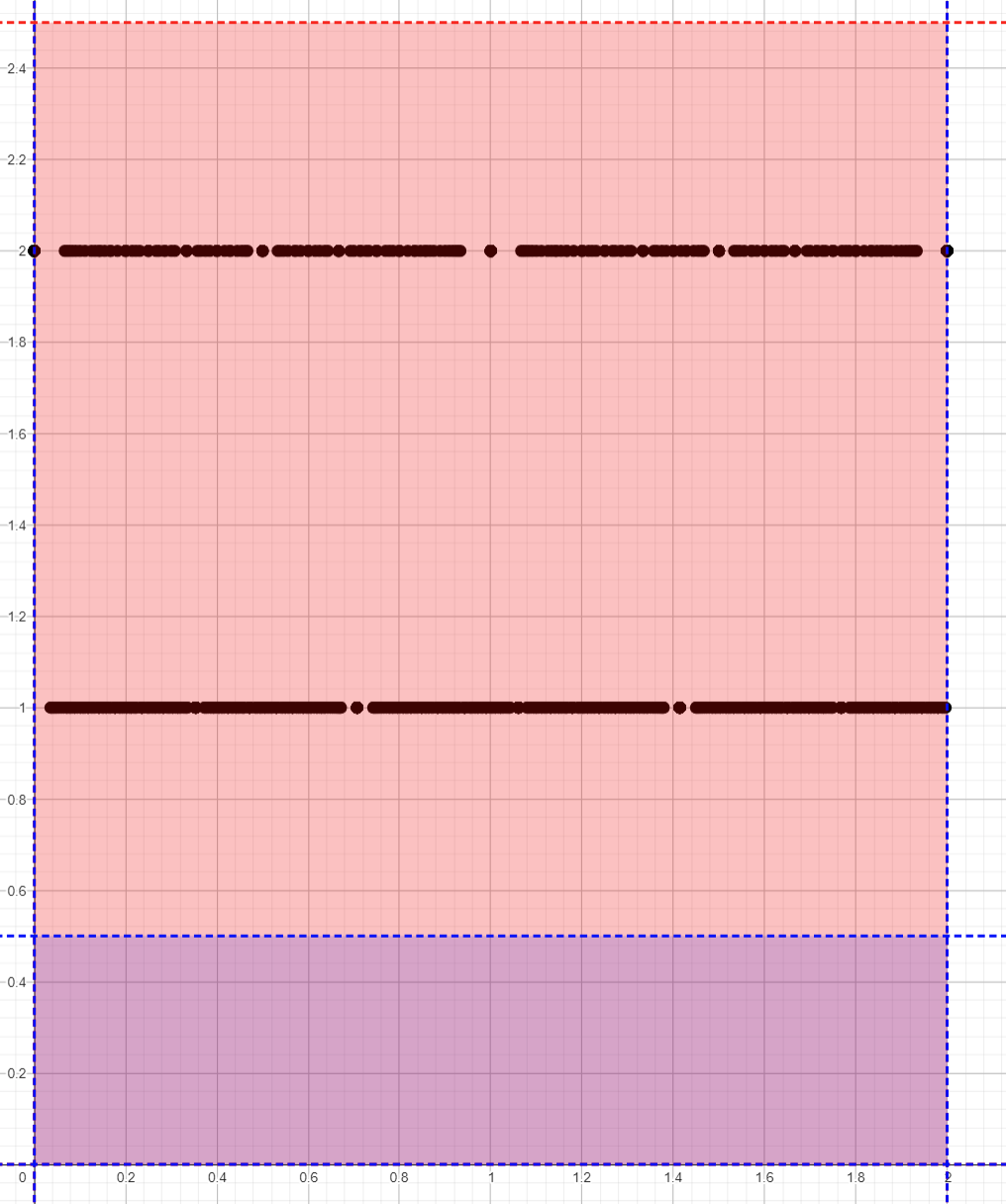

Recall the indicator function \(\chi(x)=\begin{cases}1& x\in\mathbb{Q}\\0& x\notin\mathbb{Q}\end{cases}\text{.}\) What do you think \(\displaystyle\int_{[0,2]}(1+\chi(x))\ dx\) ought to be?

Checkpoint 7.1.1 is, indeed, a doozy. But here's an easy thing we can say: whatever \(\displaystyle\int_{[0,2]}(1+\chi(x))\ dx\) ought to mean, we know it's at least 1, and it's certainly no more than 5, as Figure 7.1.2 shows.

This gives us some insight into how we might define integrals: by giving lower and upper bounds. That's what motivates this definition:

Definition 7.1.3.

A partition \(P=\{x_0,\ldots,x_n\}\) of the interval \([a,b]\) is a choice of finitely many points of the interval, starting at \(x_0=a\text{,}\) labeled in increasing order, and with \(x_n=b\text{.}\)

The upper sum of \(f\) on \(P\) is:

The lower sum of \(f\) on \(P\) is:

Observe that each time we take an upper sum or a lower sum, we're computing the total area of some collection of rectangles. So, as long as \(f\) is bounded on \([a,b]\) both the lower and upper sums will exist.

Checkpoint 7.1.4.

For the partition \(P=\{-1,-\frac{1}{2},0,\frac{1}{4},\frac{1}{2},\frac{3}{4},1\}\text{,}\) compute \(U(f,P)\) and \(L(f,P)\) for each of these functions:

\(\displaystyle f(x)=x\)

\(\displaystyle f(x)=3\)

Checkpoint 7.1.5.

The standard partition of \([a,b]\) is \(P_n=\left\{a,a+\frac{b-a}{n},a+2\frac{b-a}{n},\ldots,a+(n-1)\frac{b-a}{n},b\right\}\text{.}\) Compute \(U(f;P_n)\) and \(L(f;P_n)\) for \(f(x)=x\) and \([a,b]=[0,2]\text{.}\)

Proposition 7.1.6.

For any bounded function \(f:[a,b]\to\mathbb{R}\text{,}\) and any partitio \(P\text{,}\) the upper sum and lower sum are defined and satisfy:

Checkpoint 7.1.7.

Consider two partitions of \([a,b]\text{,}\) \(P,Q\text{.}\) If we say that "\(L(f;P)\) is a better approximation to \(\displaystyle \int_{[a,b]}f(x)\ dx\)", what do we mean?

Definition 7.1.8.

We say that \(Q\) refines \(P\) if \(P\subseteq Q\text{.}\)

Proposition 7.1.9.

If \(Q\) refines \(P\text{,}\) then

Definition 7.1.10.

The upper integral or integral superior of \(f\) on \([a,b]\) is

The lower integral or integral inferior of \(f\) on \([a,b]\) is

If \(\displaystyle\overline{\int_{[a,b]}f(x)\ dx}=\underline{\int_{[a,b]}f(x)\ dx}\) we say \(f\) is integrable on \([a,b]\) and call the common value the integral of \(f\) on \([a,b]\), denoted \(\displaystyle\int_{[a,b]}f(x)\ dx\text{.}\)

Proposition 7.1.11.

For any \(f\) and any \([a,b]\text{,}\)

Checkpoint 7.1.12.

Explain why Proposition 7.1.11 isn't obvious.

Checkpoint 7.1.13.

Prove Proposition 7.1.11.