Section 3.3 shapes of sets

Subsection 3.3.1 bounded sets

The definition of a bounded set from Chapter 1 works just fine in a metric space:

Definition 3.3.1.

If \((S,d)\) is a metric space, we say that \(A\subseteq S\) is bounded if there are some \(x\in S\) and some \(B\in\mathbb{R}\) so that \(\forall a\in A, d(x,a)\leq B\text{.}\)Proposition 3.3.2.

If \(X\) is a convergent sequence in a metric space, then \(X\) is bounded.

Checkpoint 3.3.3.

Consider the sequence in \(\mathbb{R}^\infty\) given by \(x_n=\left(0,\ldots,0,1,0,\ldots\right)\) where the 1 is in the \(n\)th slot. We'll work with the \(2\)-norm on \(\mathbb{R}^\infty\text{.}\)

Is \(X\) bounded?

What is \(d(x_i,x_j)\text{?}\)

Does \(X\) converge?

Is there a subsequence of \(X\) which converges?

Notice that, if we pick a particular coordinate to look at, that coordinate will eventually (after \(k\) terms for the \(k^{th}\) coordinate) be 0.

Remark 3.3.4.

Checkpoint 3.3.3 says that the Bolzano-Weierstraß property need not hold in a normed space. Normed spaces that do have the Bolzano-Weierstraß property will turn out to be quite special.

Subsection 3.3.2 open sets

In \(\mathbb{R}\text{,}\) we often saw that having a little bit of wiggle room -- moving from \(\epsilon\) to \(\frac{1}{2}\epsilon\) -- was important in many arguments. That's why the definitions we use have so many strict inequalities. But if we don't have an order, how do we make sense of "strictly" and obtain this same kind of wiggle room?

Checkpoint 3.3.5.

Let \(I=(a,b)\) be an open interval, and let \(c\in I\text{.}\) Explain how to obtain an open interval \(J\text{,}\) with center \(c\text{,}\) so that \(J\subseteq I\text{.}\)

Remark 3.3.6.

Checkpoint 3.3.5 is, if you like, a topological formulation of what we mean by "wiggle room". And it's one that will carry over into any metric space.

Definition 3.3.7.

Let \((S,d)\) be a metric space. A set \(A\subseteq (S,d)\) is open if for every \(a\in A\text{,}\) there is \(\epsilon\gt 0\) so that \(B_\epsilon(a)\subseteq A\text{.}\)

Remark 3.3.8.

Observe that Checkpoint 3.3.5, together with Checkpoint 3.2.14, is precisely the statement that open intervals are open, which sounds really unnecessary to state -- but in fact does not follow from the particular terminological choice "open interval".

Proposition 3.3.9.

In any metric space, open balls are open.

Proof.

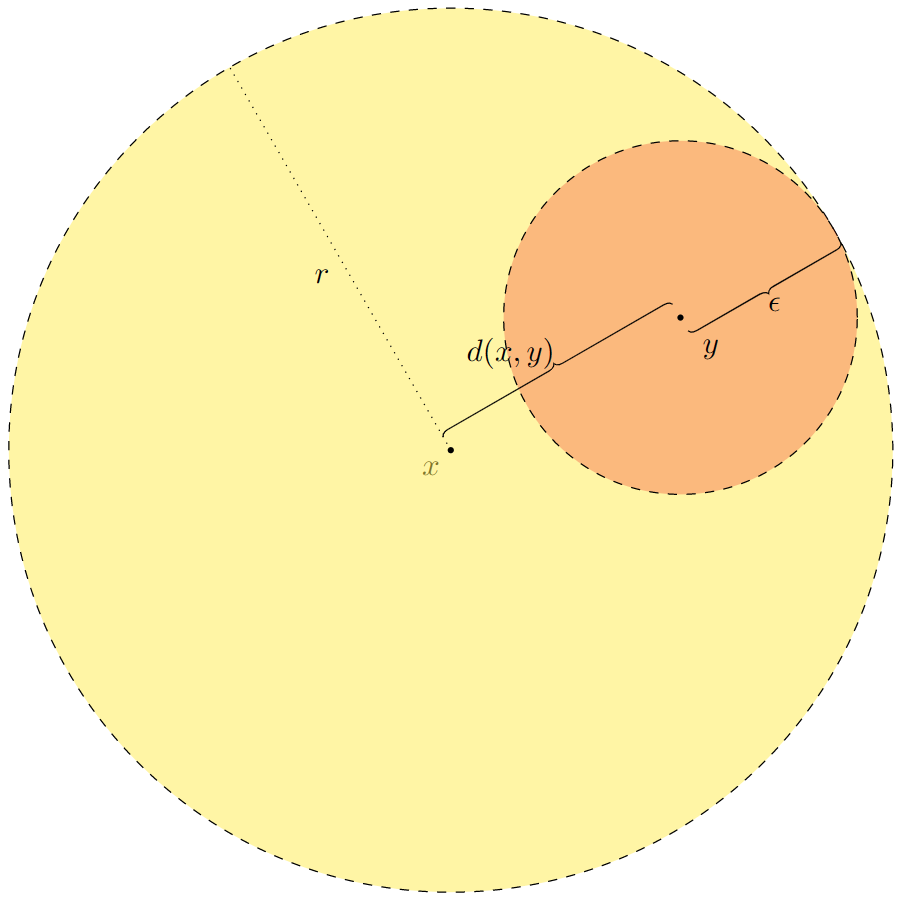

Given an open ball \(B_r(x)\text{,}\) we will show it's open.

Let \(y\in B_r(x)\text{.}\) We need to find a radius around \(y\) that doesn't take us outside of \(B_r(x)\text{.}\) Set \(\epsilon=r-d(x,y)\text{.}\) I claim that \(B_\epsilon(y)\subseteq B_r(x)\text{.}\)

To this end, let \(z\in B_\epsilon(y)\text{;}\) that is, \(d(y,z)\lt \epsilon\text{.}\) Now let's compute \(d(x,z)\text{:}\)

which is what we needed. So \(z\in B_r(x)\text{.}\)

This proof looks pretty complicated! But that's because the statement itself is complicated. Let's work through it symbolically. The statement "\(B_\epsilon(a)\subseteq A\)" means

But \(z\in B_\epsilon(a)\) just means \(d(z,a)\lt \epsilon\text{.}\) So the innermost part of the definition of open set reads

Now let's handle the variables \(a\) and \(\epsilon\text{:}\)

So a proof that \(A\) is open will always have the form

And the work of the proof will end up being: how do we pick \(\epsilon\) for a given \(a\in A\text{?}\)Given \(a\in A\text{,}\) . . . consider \(\epsilon=\cdots\)

Let \(z\) have \(d(z,a)\lt \epsilon\text{.}\) Then . . .

[a whole bunch of work here]

. . . so we see that \(z\in A\text{.}\)

My advice, as regards proofs like this, is:

Obviously not every normed space or every metric space is \((\mathbb{R}^2,\lVert\cdot\rVert_2)\text{,}\) but usually your eyes will do a decent job of suggesting what to do. For example, Figure 3.3.10 is the sketch I used to arrive at the choice \(\epsilon=r-d(x,a)\text{.}\)Draw a picture in the plane.

Checkpoint 3.3.11.

What does it mean for a set to not be open?

Checkpoint 3.3.12.

Here are some subsets of \(\mathbb{R}\text{.}\) Identify them as either open or not open. Give a proof for each.

\(\displaystyle \{1\}\)

\(\displaystyle \mathbb{R}\)

\(\displaystyle (-1,\infty)\)

\(\displaystyle [2,3]\)

\(\displaystyle \varnothing\)

Proposition 3.3.13.

If \(U_1\) and \(U_2\) are open, \(U_1\cup U_2\) is open.

Actually the proof of Proposition 3.3.13 doesn't rely on the fact that there were only two sets.

Theorem 3.3.14. Union of Open Sets is Open.

If \(\left\{U_\alpha\right\}_{\alpha\in\Lambda}\) is a collection of open sets, then \(\displaystyle\bigcup_{\alpha\in \Lambda} U_\alpha\) is open.

Proposition 3.3.15.

If \(U_1\) and \(U_2\) are open, \(U_1\cap U_2\) is open.

Proposition 3.3.16.

If \(U_1,\ldots, U_k\) are open, then \(\displaystyle\bigcap_{i=1}^k U_i\) is open.

Proof.

We proceed by induction on the number \(k\) of sets in the collection.

If there's only one set, we're done.

If there are two sets in the collection, this is just Proposition 3.3.15.

Now let \(k\geq 3\) and assume that we've shown all intersections of \(k-1\) or fewer open sets are open. Consider a collection \(U_1,\ldots, U_k\) of open sets. Then \(U_1\cap\cdots\cap U_k=U_1\cap(U_2\cap \cdots\cap U_k)\text{;}\) by the inductive assumption, \(U_2\cap \cdots\cap U_k\) is open. So the \(U_1\cap\cdots\cap U_k\) can be written as the intersection of 2 open sets, hence is open.

But! One should be cautious: the hypothesis that there are finitely many open sets involved in the intersection is critical, as the example

shows.

Subsection 3.3.3 closed sets

If open sets generalize open intervals, what plays the role of closed intervals?

Definition 3.3.17.

A set is closed if its complement is open.

Checkpoint 3.3.18.

Show that a closed interval \([\alpha,\beta]\) is closed in \(\mathbb{R}\) with the standard norm.

Proposition 3.3.19.

In any metric space, the closed ball \(D_r(x)\) is closed.

Proof.

We must show that

is an open set.

To this end, let \(y\in \left(D_r(x)\right)^c\text{;}\) that is, assume \(d(x,y)\gt r\text{.}\) Set \(\epsilon=d(x,y)-r\text{;}\) we'll show that \(B_\epsilon(y)\subseteq \left(D_r(x)\right)^c\text{.}\)

Let \(z\in B_\epsilon(y)\text{,}\) i.e. \(d(z,y)\lt \epsilon\text{.}\) Then we have

which we can rearrange to say

But this is precisely the condition for \(z\in \left(D_r(x)\right)^c\text{.}\)

Checkpoint 3.3.20.

Draw the picture for the proof of Proposition 3.3.19.

Corollary 3.3.21.

Let \(C_1,\ldots,C_k\) be a finite collection of closed sets. Then \(\displaystyle\bigcup_{i=1}^k C_i\) is closed.

Let \(\{C_\alpha\}_{\alpha\in\Lambda}\) be any collection of closed sets. Then \(\displaystyle\bigcap_{\alpha\in\Lambda}C_\alpha\) is closed.

Checkpoint 3.3.22.

Which mathematical result is Corollary 3.3.21 a corollary of?

Checkpoint 3.3.23.

Are these sets closed?

\(\displaystyle V\)

\(\displaystyle \varnothing\)